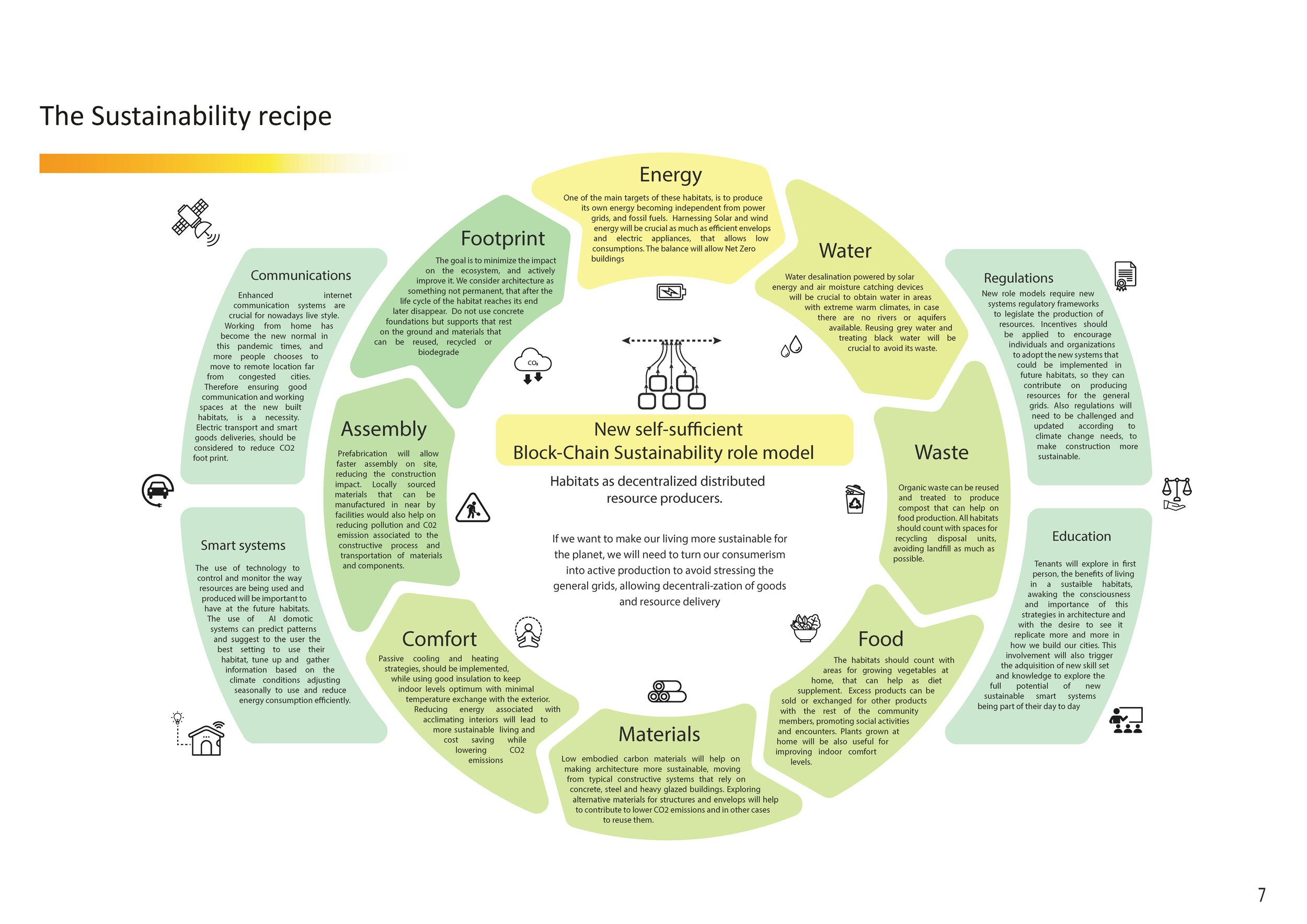

Given the current rate of greenhouse gas emissions saturating our atmosphere, the scientific community agrees that we will have to face a global rise in temperatures that will alter existing climate dynamics. Over the course of the next century, this shift will transform ecosystems and landscapes as we know them today, forcing contemporary construction systems to adapt to new environmental conditions. As an architect, I believe it is essential to explore alternatives that can improve our quality of life in future scenarios where climatic conditions may become extreme and where basic natural resources could be even more scarce than they are today.

Find this article in Archdaily, Designboom y Plataforma Arquitectura

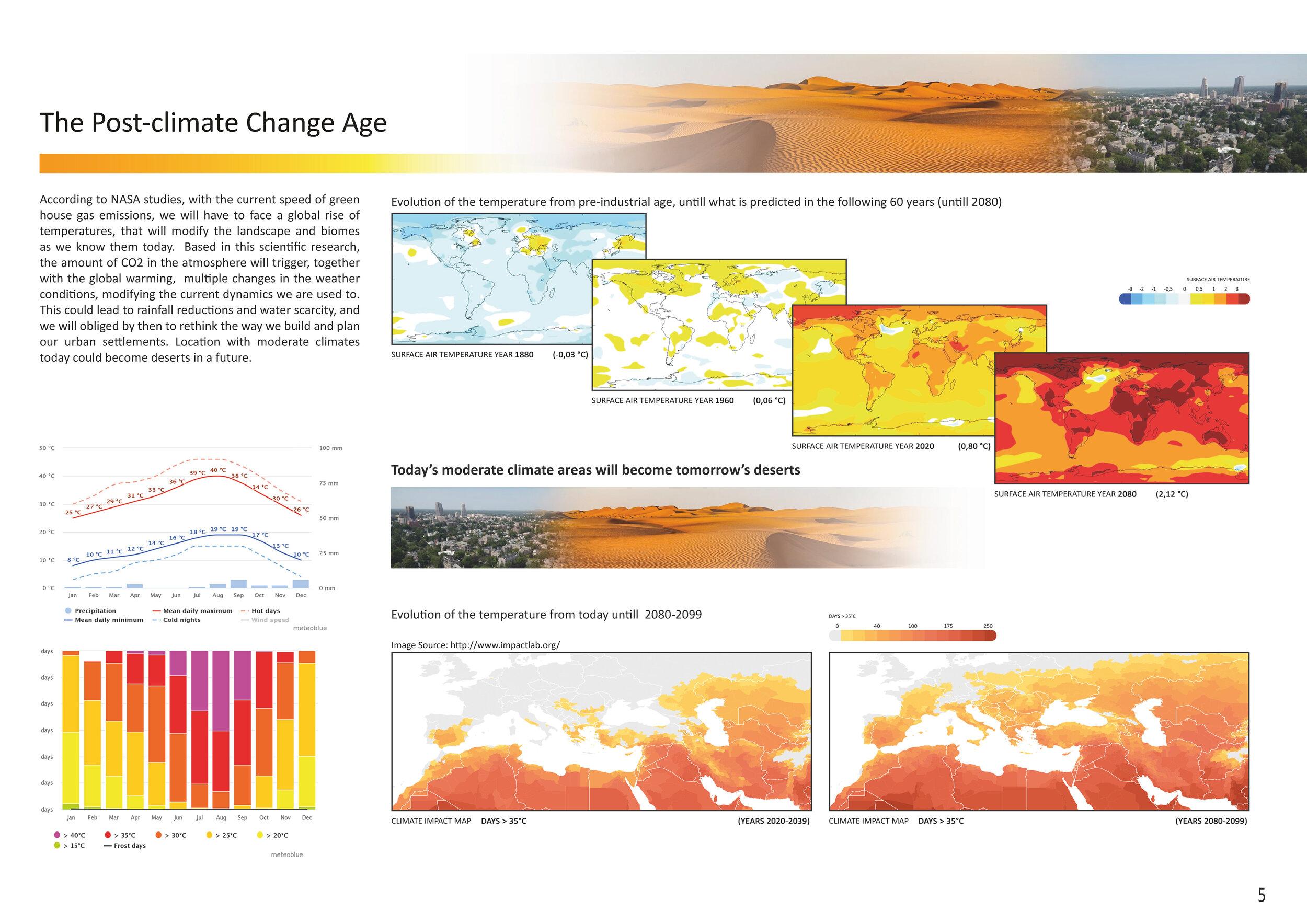

The Post–Climate Change Scenario

The predictions generated through computational simulations present scenarios that differ significantly from those we experience today. These analyses indicate that many temperate climate regions could transform into arid areas with harsh environmental conditions. Extreme temperatures and new climatic dynamics will require a fundamental rethinking of urban settlements and construction methods in these regions. Aware of this possible future, I explore how housing could evolve in a context of limited natural resources and extreme climatic conditions. For this post–climate change design study, I use solar analysis tools to investigate how a low-tech habitat, built with bio-construction materials, can respond to these challenges. The goal is to propose more sustainable, flexible solutions capable of adapting to environments characterized by extreme heat and resource scarcity.

Protection Against Environmental Adversity

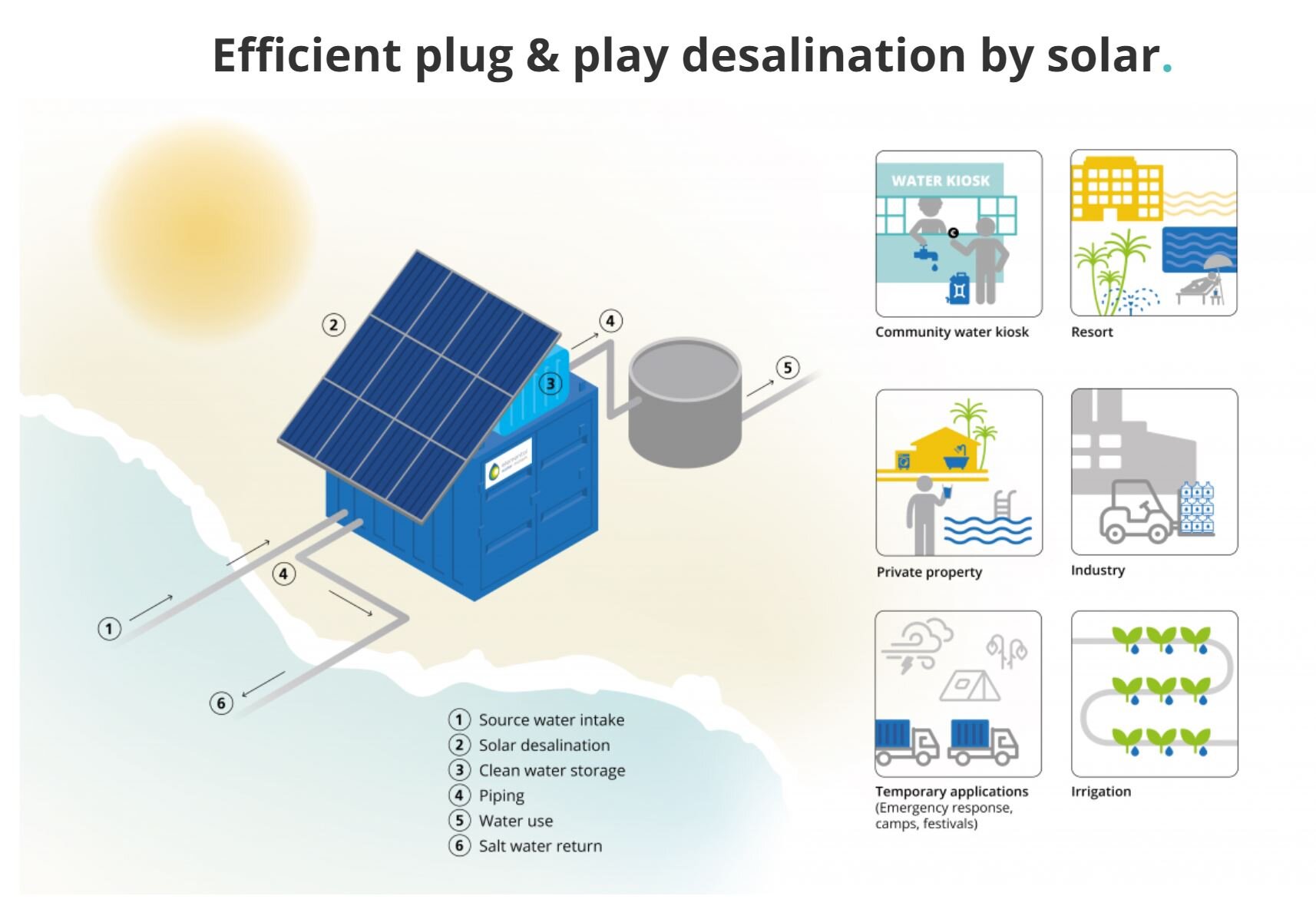

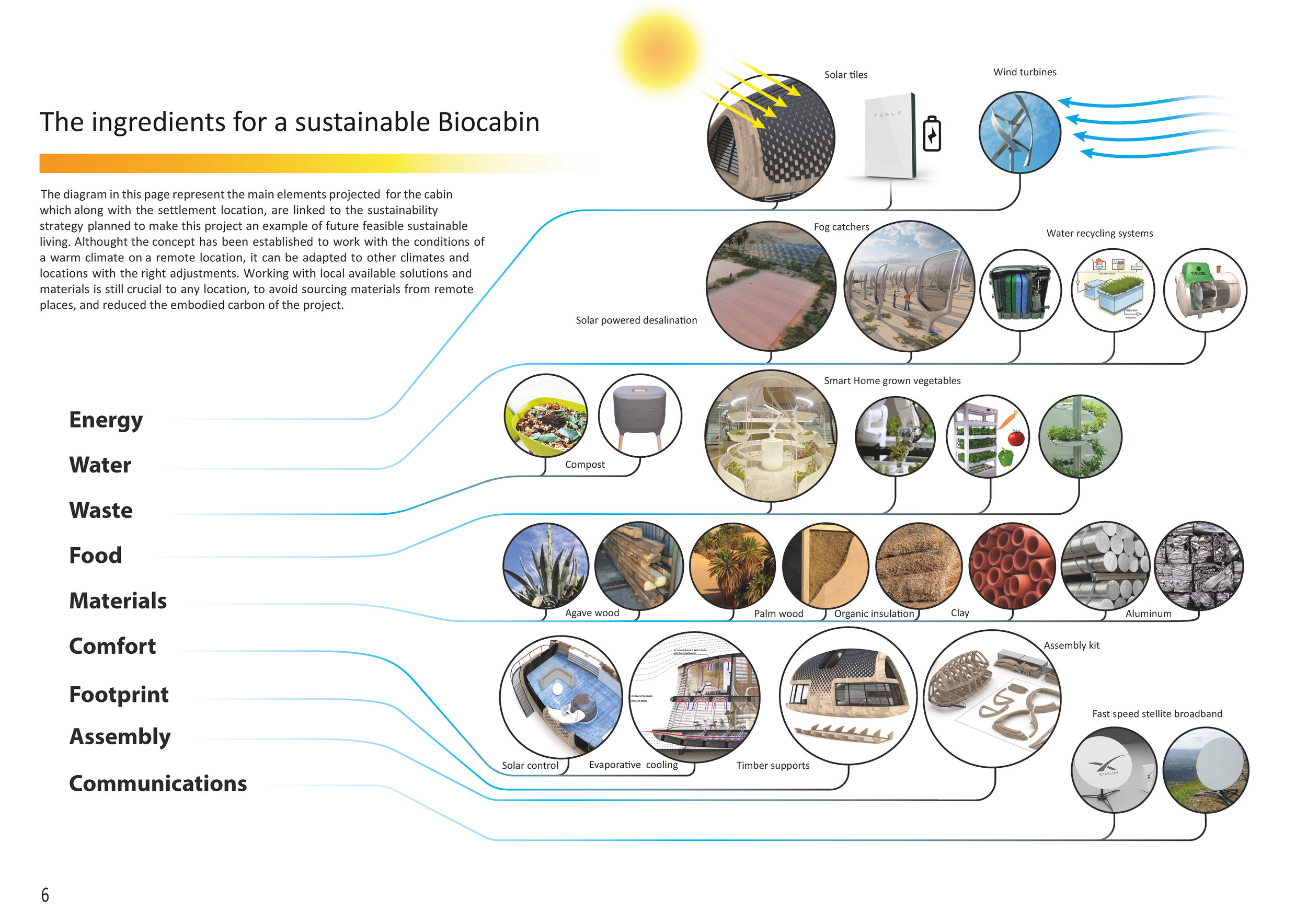

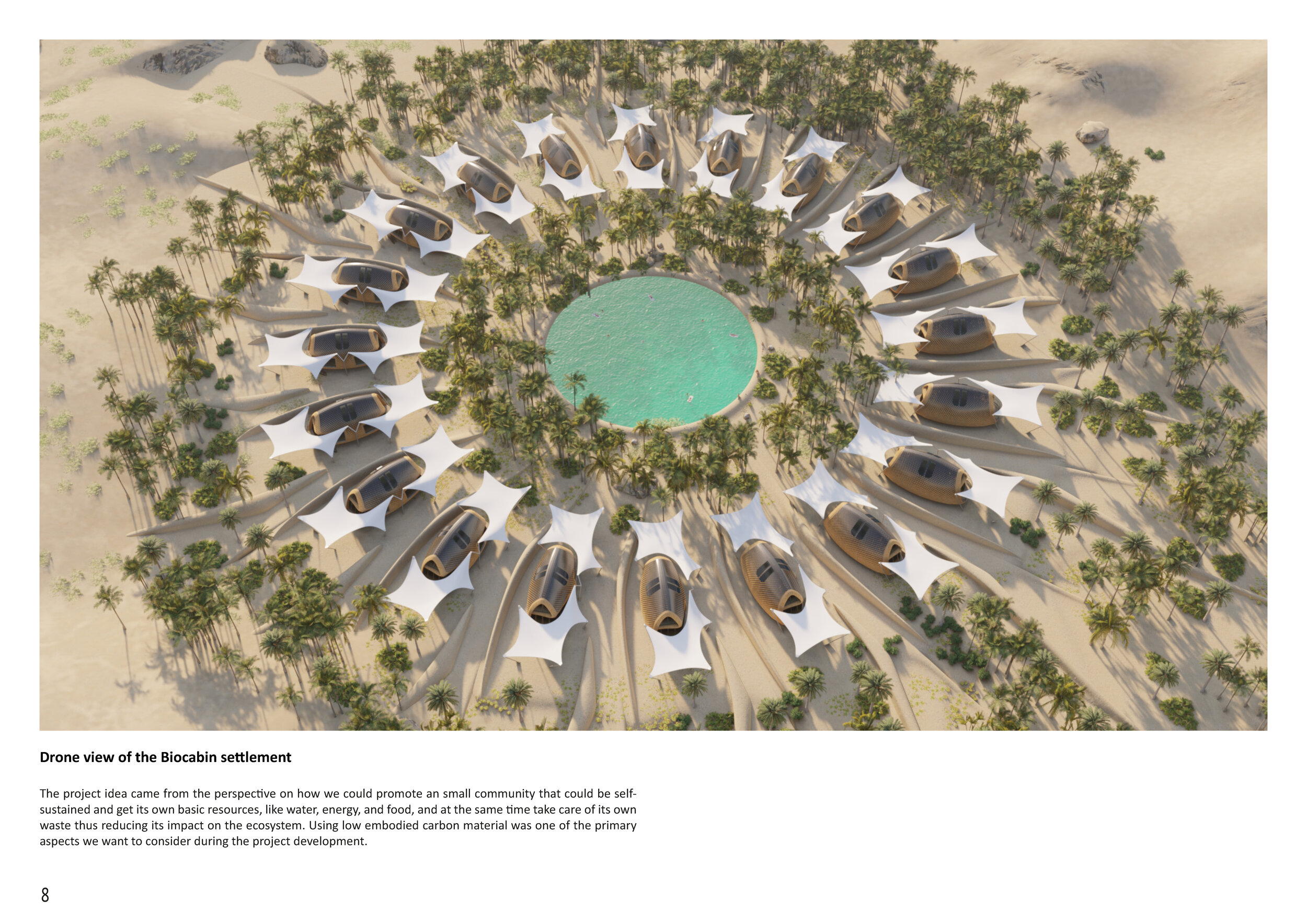

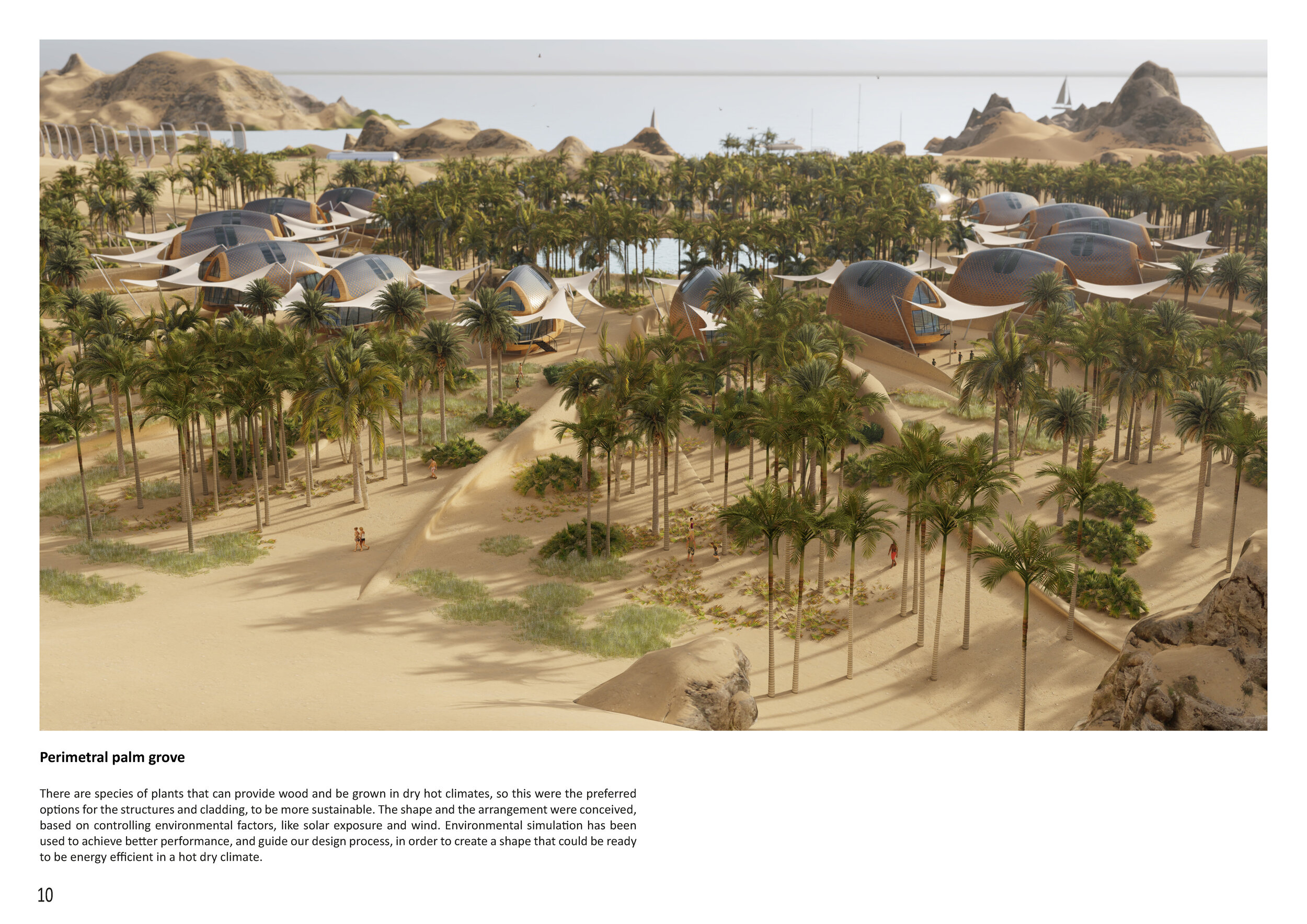

For a settlement located in an arid environment, I propose transportable living units that rest lightly on the ground using screw pile foundations. These foundations can be removed without leaving permanent marks on the site, further minimizing the environmental footprint. I envision a radial arrangement of low-rise habitable modules, designed to define a protected central space for outdoor communal activities. The integration of vegetation, shading elements, and low perimeter walls helps shield the settlement from strong winds and intense solar radiation. Together, these strategies create sheltered spaces organized around an artificial oasis, supplied with water from a solar-powered desalination system and fog-harvesting devices. This system enhances outdoor comfort and contributes to lowering temperatures in the immediate surroundings of the settlement.

Vegetation as Wind Protection

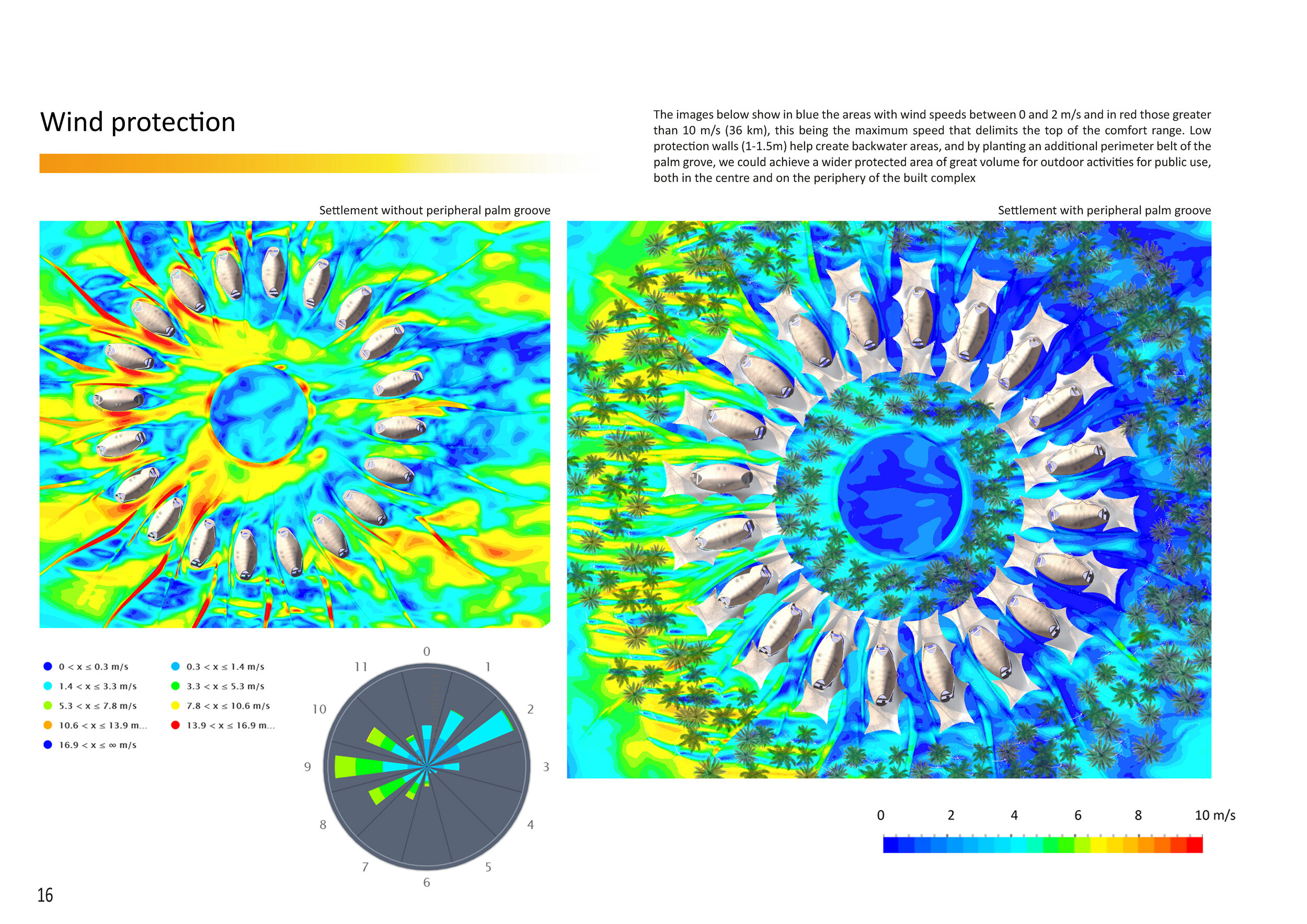

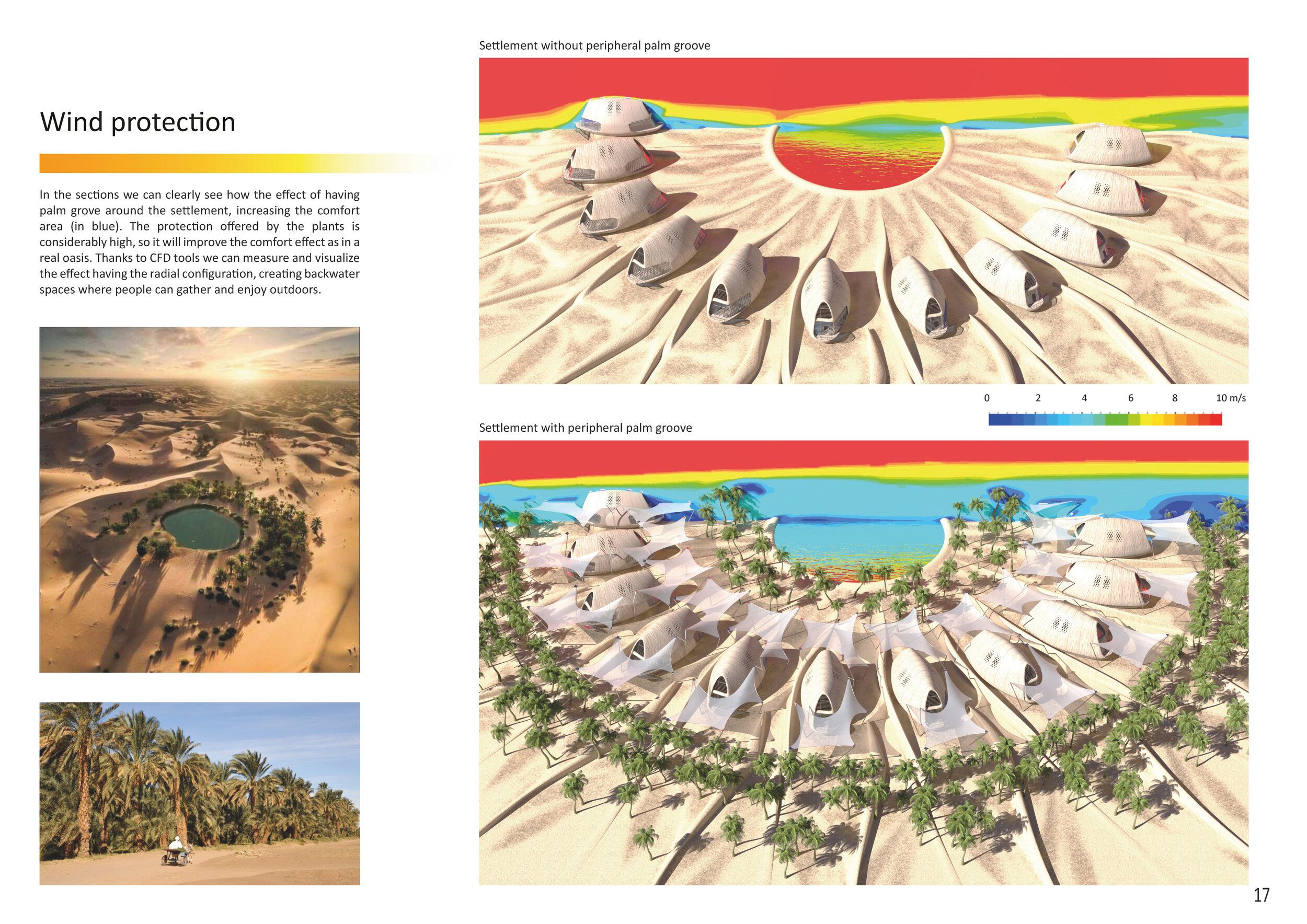

My wind dynamics studies confirm the effectiveness of palm groves and desert vegetation in reducing wind intensity in highly exposed environments. Green belts are known to act as filters for airborne particles while also providing shelter. Through computational CFD tools, I am able to validate the performance of this strategy and quantify the volume of protected space it creates.

In the images below, blue areas represent wind speeds between 0 and 2 m/s, while red areas indicate speeds above 10 m/s (36 km/h), which defines the upper threshold of the comfort range. The use of low protective walls (1–1.5 m) helps create localized wind-shadow zones, but proves insufficient on its own. As shown in the vertical sections, the addition of a peripheral palm grove allows for the creation of a large, protected volume suitable for public outdoor activities, both at the center and along the perimeter of the built complex.

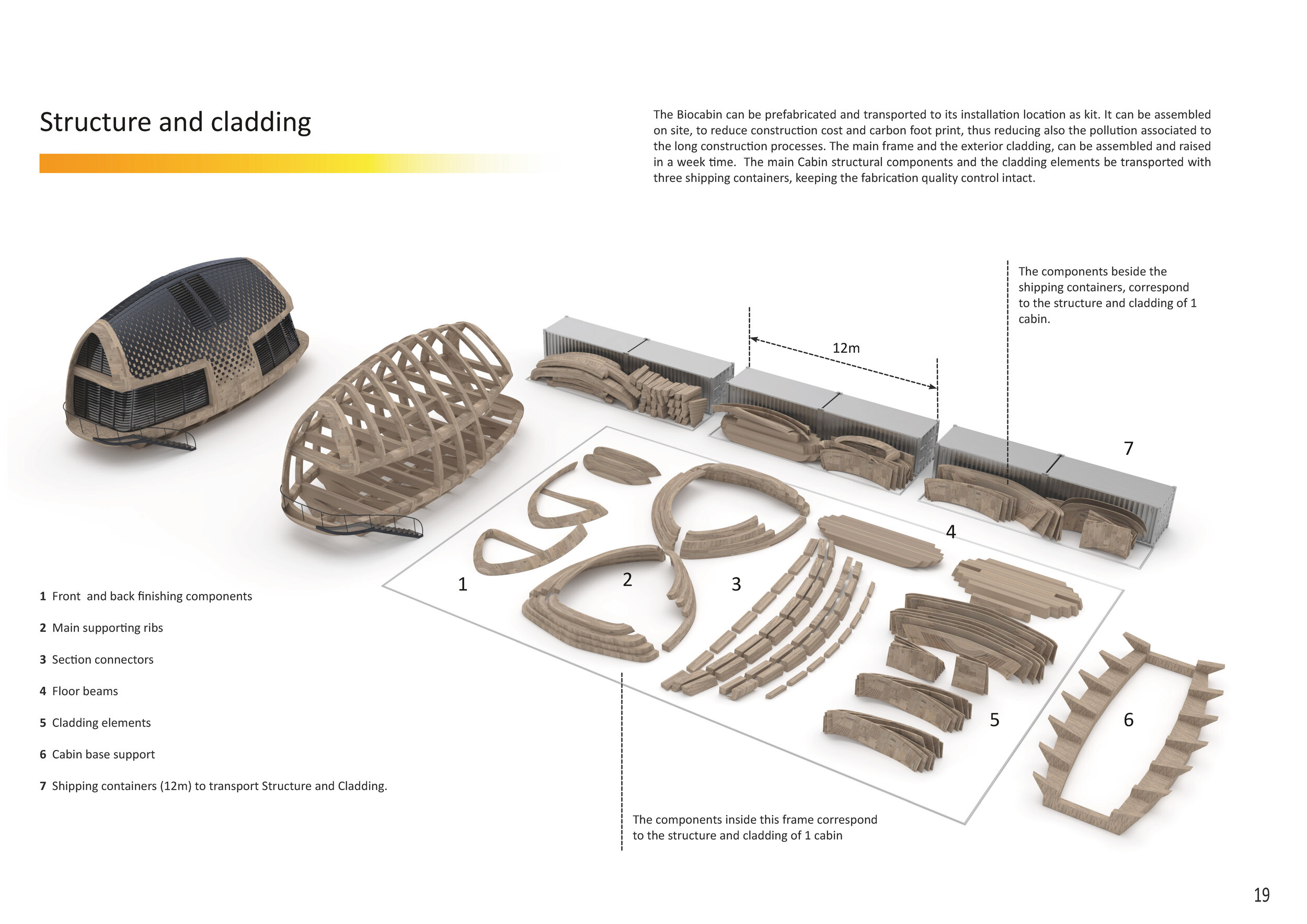

Prefabricated Habitats for Rapid Assembly

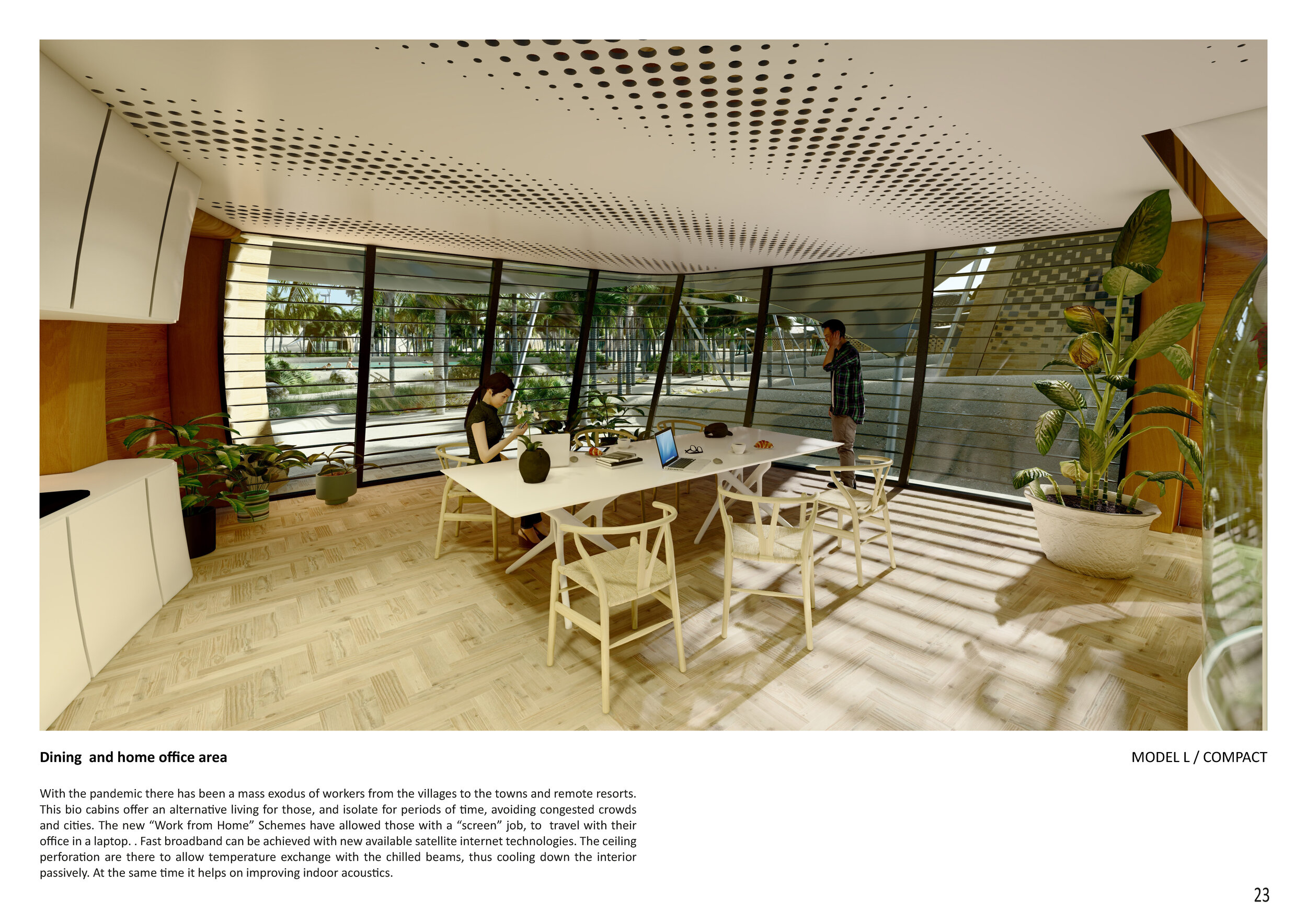

The ability to remain mobile and work from remote locations has become an essential requirement in the current global context. Future settlements should therefore be planned at a smaller scale, avoiding high density, while being sustainable, self-sufficient, and technologically hyperconnected. These qualities are key to providing healthier living conditions and a higher quality of life for their inhabitants.

Sustainable Materials

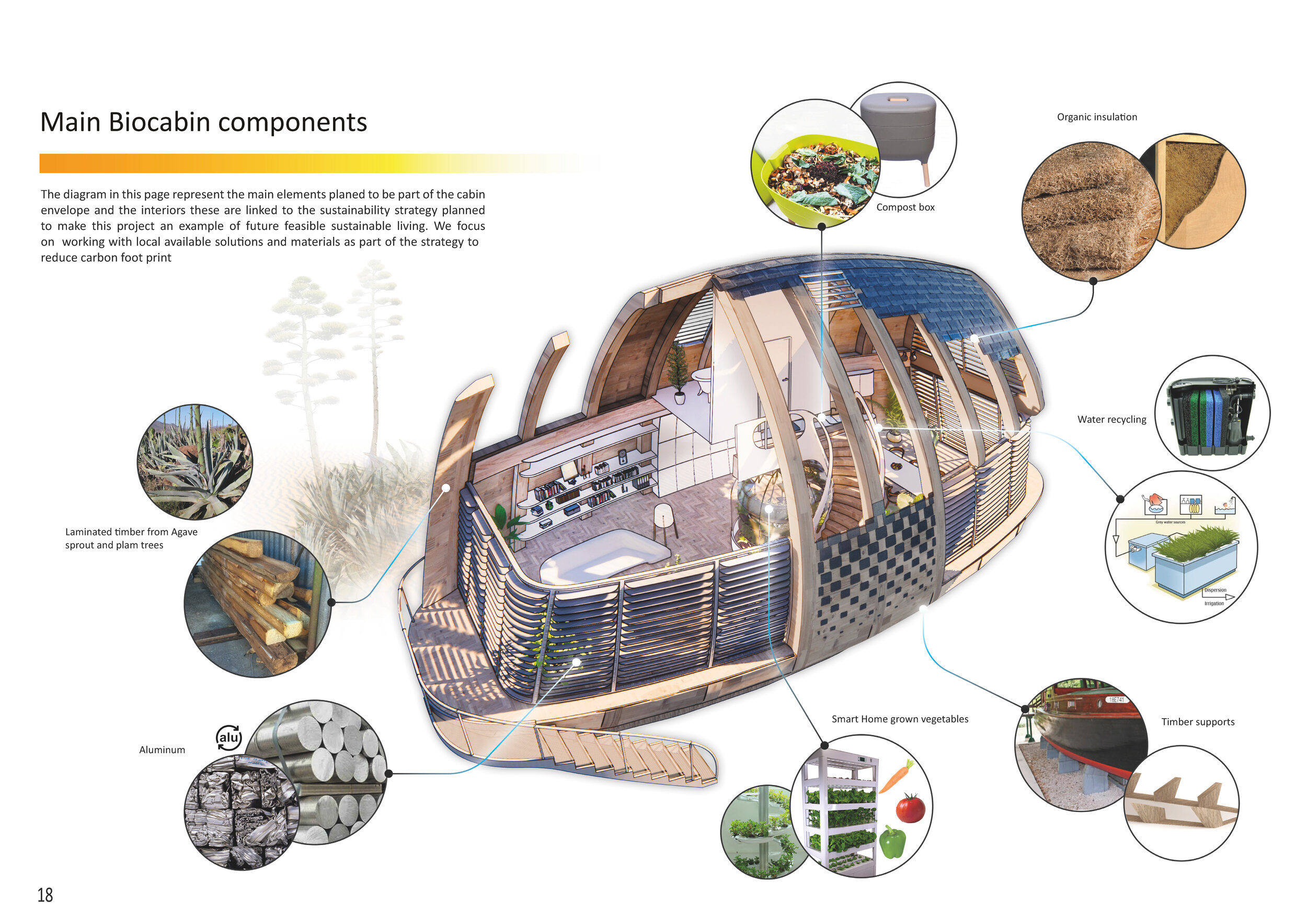

In this concept for housing in extreme climates, I explore the use of natural materials or materials with a high degree of reuse and recyclability. To achieve a truly sustainable solution, I prioritize locally available resources to avoid the high energy costs associated with long-distance transport.

Structure and Cladding: I propose using alternative woods derived from American agave plants. Often referred to as “desert wood,” it thrives in arid climates and has been widely used in bio-construction for centuries. It can be processed into panels and laminates that are as durable as conventional construction woods. Its fibers are also reusable, allowing them to be transformed into other construction materials.

Interior Insulation: Using fibers from the agave plant—even including its roots—I can create thermal insulation without chemical additives. Commercial examples exist, such as panels produced by Rootman, made from a blend of various roots. These panels provide both thermal and acoustic insulation for interior spaces, enhancing comfort in extreme conditions.

Base Supports: To avoid permanent concrete foundations while maintaining durability, I propose a screw-pile system that can be inserted directly into the ground. The main advantage is mobility: these supports can be removed once the cabin reaches the end of its service life, or if the structure needs to be relocated.

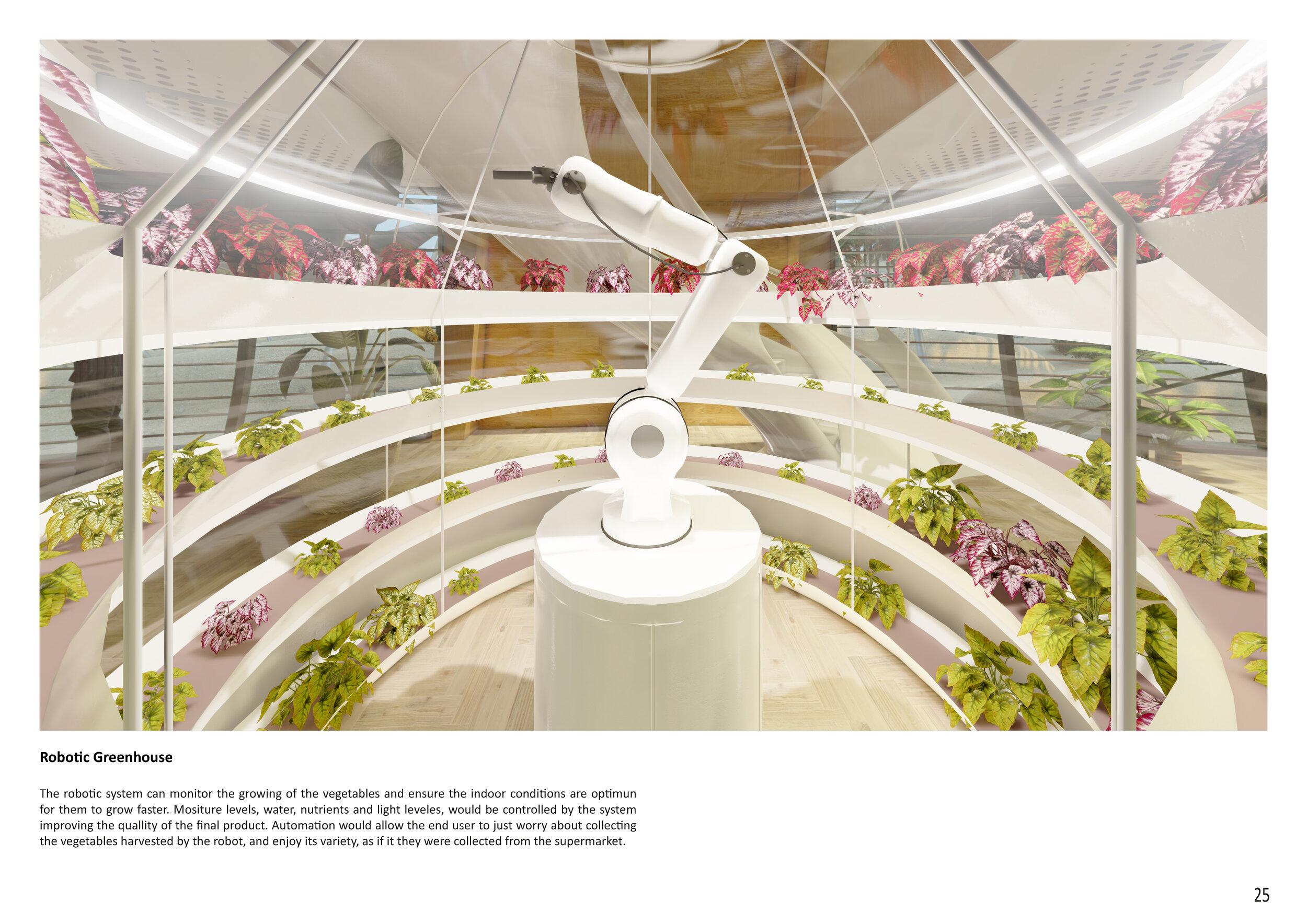

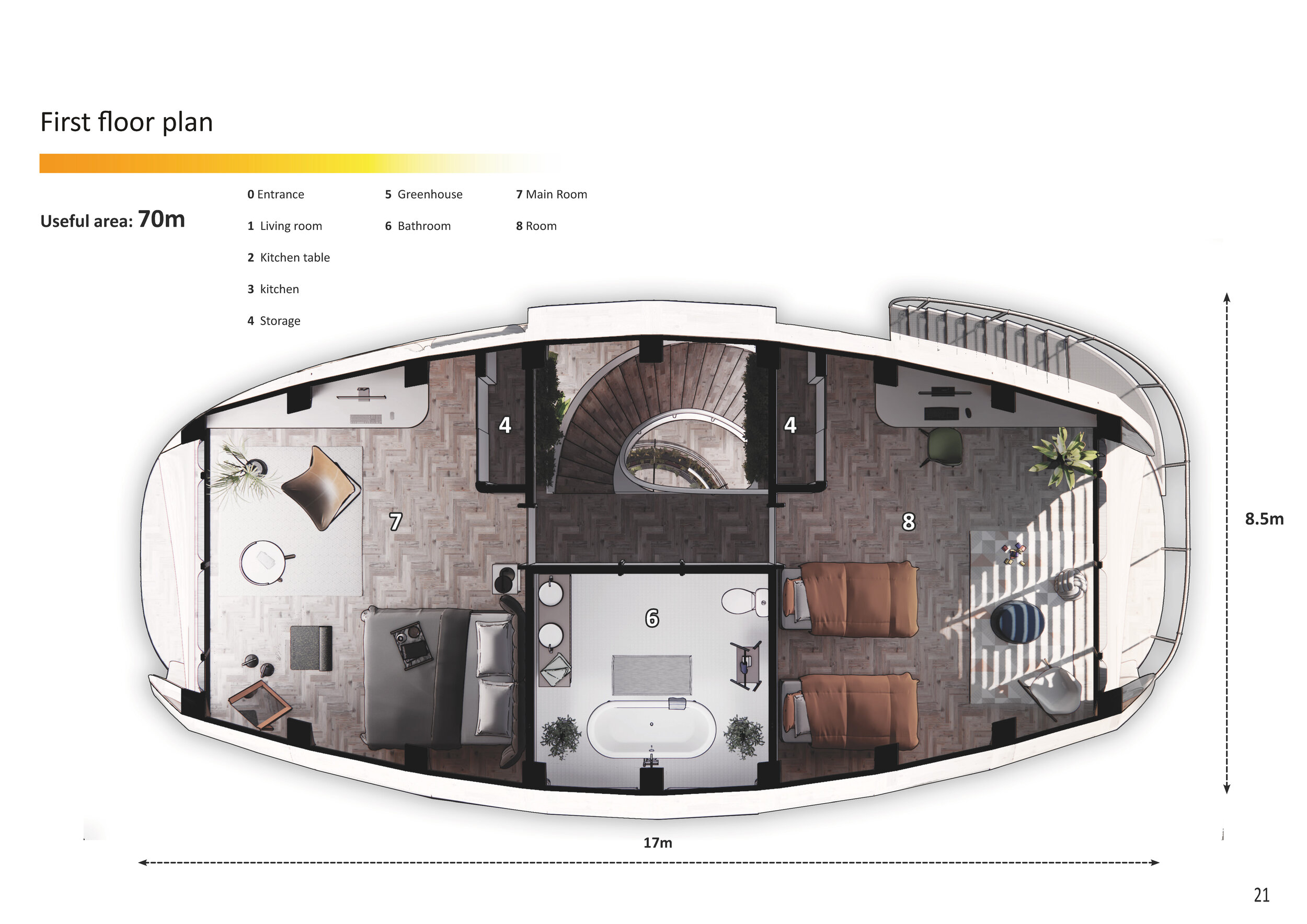

Greenhouses: I conceive the interior of this home as a space capable of housing plant- and vegetable-growing units for human consumption. This allows residents to live healthily, with fresh produce available directly in their living room or kitchen. The house would include a detailed instruction manual for planting and caring for the crops until harvest, promoting self-sufficiency and enhancing survival skills.

Organic Waste Composting: Organic waste and plant trimmings are composted to serve as fertilizer for the plants. Various safe indoor composting systems can be used, supporting the goal of a sustainable and closed-loop living environment.

Greywater Recycling: Greywater and wastewater are treated through systems located beneath the house, enabling reuse for irrigating crops within the greenhouses and other planting areas.

Recycled Aluminum: Any elements that must be metallic are designed using aluminum due to its high recyclability and potential for reuse.

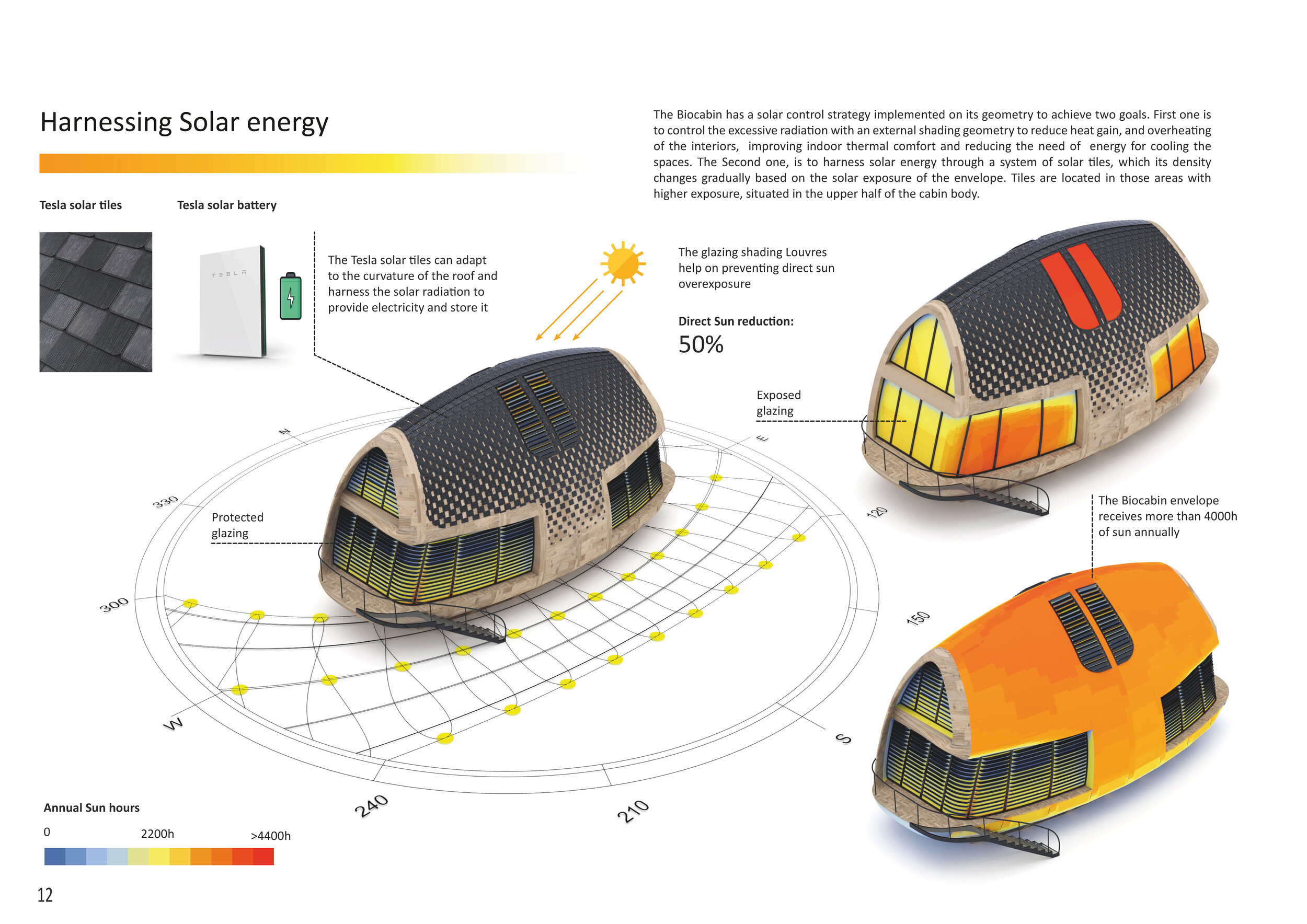

Energy Production: This housing unit includes solar panels and external wind turbines to generate renewable energy, which is stored in batteries installed underground. These systems provide energy for nighttime use, ensuring the home remains functional and self-sufficient.

Fresh Water Systems: In designing a post–climate-change settlement, I explored systems for obtaining potable water that could ensure self-sufficiency. I proposed two potential solutions to secure water directly from the air and from the sea. A reliable water supply is essential for resilient and autonomous living, so I designed a combined system to provide continuous water access throughout the year:

Fog Harvesting: In both mountainous and arid coastal climates, fog can be captured using polyethylene nets (a recyclable plastic) when the right atmospheric conditions occur. This system can collect between 4 and 14 liters per square meter by condensing dispersed moisture in the air. With enough units installed, it is possible to maintain a constant water supply for a community, such as the one envisioned in this settlement. Similar systems have been implemented in areas along the coasts of Morocco, as well as in Chile and Peru, demonstrating the viability of fog harvesting as a sustainable water solution.

Solar-Powered Desalination: If no extractable water is available from nearby aquifers or rivers, seawater desalination becomes an alternative. I explored the use of modular desalination units powered by solar energy, which can provide freshwater for settlements of varying sizes. These systems offer a sustainable solution to secure water in areas with limited natural sources.

Brine Reuse to Prevent Environmental Impact: The brine produced during desalination can be treated to extract chemicals for use in other industrial processes. Research conducted by engineers at MIT demonstrates that this approach is both feasible and environmentally beneficial, addressing the common ecological concerns associated with desalination.